By 1795, the political climate of the young American Republic had shifted. Intensifying anxieties regarding foreign radicalism — particularly from revolutionary France and Ireland — led Congress to view new arrivals with increasing suspicion. The Naturalization Act of 1795 was designed to slow the pace of integration, significantly narrowing the pathway to citizenship for the «free white persons» eligible under federal law.

While the 1790 Act established the first federal framework, the 1795 legislation turned citizenship from a simple legal transition into a multi-step bureaucratic endurance test.

Administrative Barriers and Class Disparity.

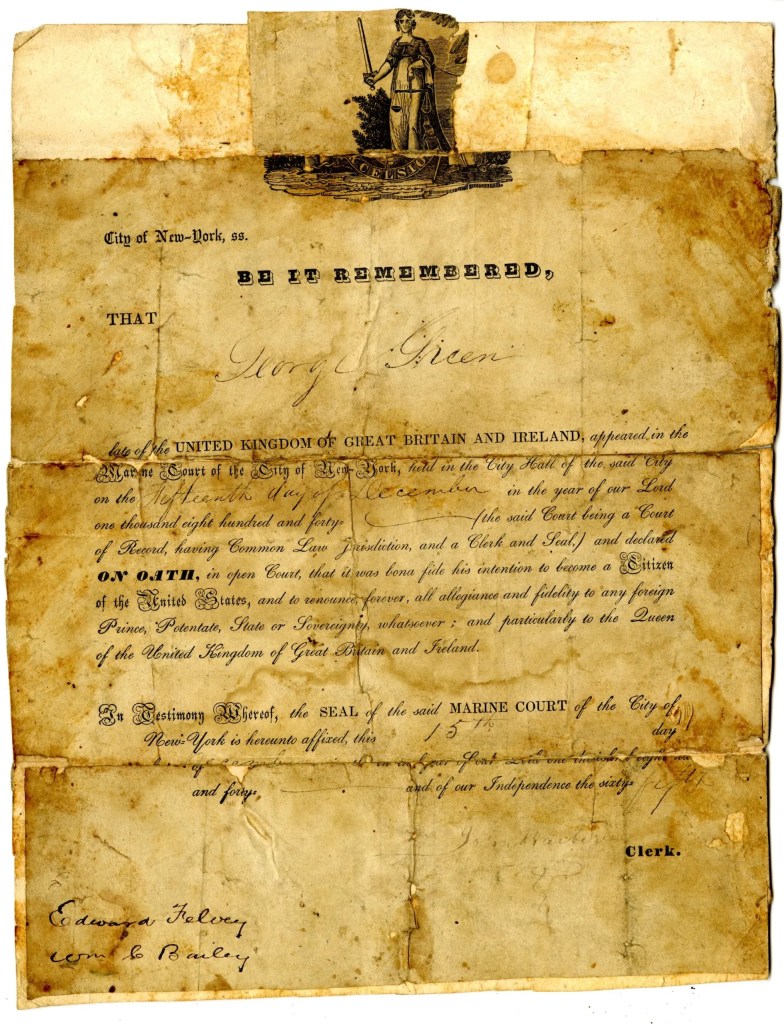

The 1795 Act introduced hurdles that hit the working-class immigrant hardest. It formalized a mandatory two-step process: filing a «Declaration of Intent» (commonly known as «first papers») at least three years before a final application could even be considered. Furthermore, the total residency requirement was more than doubled, jumping from two years to five years. These requirements created a significant class divide. The Mobility Trap: For a labor force that followed seasonal work or canal projects, proving five years of continuous residency was often impossible.

Subjective Character Tests: Applicants had to appear before a «court of record» to prove their «good moral character.» This standard was often subjectively applied by local judges who could deny citizenship based on an immigrant’s poverty, political leanings, or lack of influential social connections.

As a result, a massive portion of the white immigrant population remained «factual non-citizens» throughout their lives. They integrated into local economies and farmed American land, but remained «alien» in the eyes of the law due to the sheer difficulty of the bureaucratic gauntlet.

The Racial and Social Legacy.

The 1795 Act explicitly reinforced the racial gatekeeping of its predecessor, limiting eligibility to «free white persons.» This created a sharp legal contrast within immigrant families. The Immigrant Parent: Faced high administrative barriers (if white) or an absolute legal barrier (if non-white).

The Native-Born Child: Held a status that predated the Constitution itself. In states like Massachusetts, a child born to a Black immigrant parent in 1796 was a citizen by birth, even as their parent was legally barred from ever naturalizing.

Correcting the Birthright Misconception.

A critical takeaway from this era is the persistence of birthright citizenship as a separate legal track, untouched by these rising naturalization barriers.

The Historical Reality: The 1795 Act made naturalization for adults significantly more difficult, but it did not — and legally could not — override the established principle of Jus Soli (right of the soil). The 14th Amendment’s eventual role in 1868 was not to «grant» this right for the first time, but to serve as a constitutional shield. It ensured that the «white only» logic of naturalization, which had been reinforced by the 1795 Act, could never be used to deny citizenship to non-white persons born within the United States. It took a pre-existing Northern reality and turned it into an unassailable national mandate.

Image source and (C): The Library of Virginia