Before 1790, naturalization in the United States was a patchwork of inconsistent procedures, shaped by local politics, patronage, and varying state laws. This fragmentation created a legal vacuum that necessitated a uniform federal standard, eventually established by the Naturalization Act of 1790.

During this early period, formal citizenship was rarely a prerequisite for daily life. Many «free» white immigrants worked, rented property, and farmed while remaining active in their communities for decades without official papers. Local authorities often tolerated this situation, allowing for a form of «factual» integration that bypassed formal legal channels entirely. For the poor immigrant, acquiring formal citizenship was generally a secondary concern, unless they specifically sought to hold public office or secure the right to own and bequeath land in jurisdictions with strict «alien land laws».

The Birthright Divide: Jus Soli vs. Partus.

A common misconception today is that birthright citizenship was a «new» right created by the 14th Amendment in 1868. In reality, the U.S. had already been grappling with two competing legal traditions regarding birthright citizenship. The Northern Tradition (Jus Soli): In states like Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania, the U.S. adhered to the English common-law doctrine of «right of the soil.» Under this principle, birth within U.S. territory automatically conferred citizenship, regardless of the parents’ legal status. In these states, children born to free Black parents were recognized as citizens from the beginning of the Republic.

The Southern Tradition (Partus Sequitur Ventrem): In states like Virginia and South Carolina, the common law was subverted by the Roman principle of «the offspring follows the womb.» This doctrine ensured that children born to enslaved women remained the property of their masters, effectively denying birthright citizenship to a large portion of the population and leaving free Black children in a precarious legal limbo.

The Historical Reality: The 14th Amendment of 1868 did not «invent» birthright citizenship; it nationalized the Northern tradition of Jus Soli. It protected a pre-existing reality — where a Black child born in Massachusetts was a citizen by birth — overruling the racial logic of the South and later rulings like Dred Scott (1857), which had sought to impose the Southern «womb-based» logic as the national standard.

The Naturalization Act of 1790: Federal Racial and Class Logic.

While the «soil» provided a path for children in some states, the Naturalization Act of 1790 created a rigid federal barrier for their parents. By limiting naturalization to «any alien being a free white person,» Congress ensured that the «earned» path to citizenship was a racial monopoly. However, even for «white» immigrants, the path was often blocked by class. The Property Barrier: Most states maintained property requirements for voting. A poor white immigrant might successfully naturalize under federal law but still be denied the right to vote if they did not own sufficient land.

The Family Gap: Under coverture, a white woman’s status followed her husband’s. For non-white families, no such «bridge» existed. A Black woman born abroad remained a permanent «alien» because she could not «lawfully naturalize» under the 1790 rule, even if she lived in a state that recognized her husband’s citizenship.

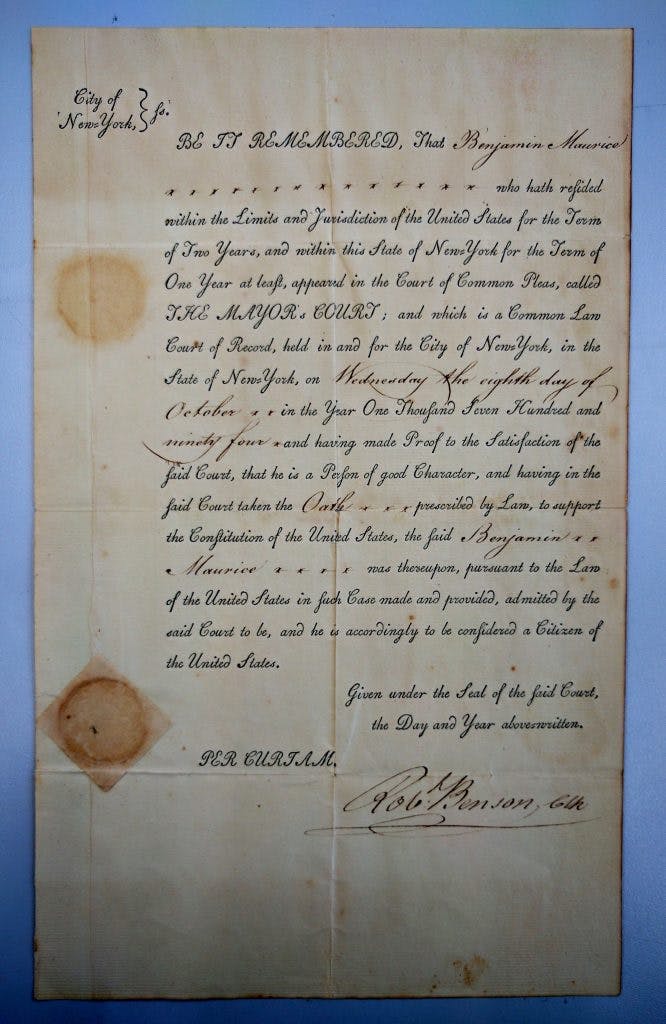

To bring order to the «patchwork» system, the Act of 1790 required:

Residency: Two years in the U.S. and one year in the state of application.

Character: Proof of «good character» presented to a court of record.

Allegiance: An oath to support the Constitution.

For the poor white laborer, these requirements — and the associated court fees — often felt unnecessary. They lived as «factual citizens,» participating in the economy and society, while their children became «legal citizens» automatically through birthright, despite the parents’ inability to afford or navigate the naturalization process. This left the adult immigrant in a state of perpetual legal limbo, while their children held a status the parents could never achieve.

Image Source and (C): The New York Historical